Wednesday, January 21, 2004

Zane Hits the Jackpot

Thank you, Zane. You said it very well. Couldn't have done better myself. But I can at least make some bad metaphors and pad the zinger with some fluffy commentary.

Logically speaking, Bush's speechwriters messed up bigtime on this one. It would have more defensible to blame other nations' broken promises for our invasion of Iraq rather than lay claim to a morally superior, ironclad devotion to our own. But this poses the rhetorically unpopular spectre of arguing in failure space rather than success space, so it probably wasn't even considered.

I think what makes Zane's hypocricy spotlight so damn appealing is that this kind of doublespeak is not just emblematic, but fundamental to our current adminstration's workings: lack of credibility is more a postulate than a theorem or corollary, an underlying force rather than a peculiar deux-ex-machina curiousity arising from the Bush II factory.

Bush saying "no one can now doubt the word of America" was like the lying logic-problem character saying "I never lie," an "aha!" moment for anyone who was paying attention. Never has this principle been more eleganty stated than in last night's State of the Union speech.

And thank you, again, Zane, for triggering this realization of mine. You totally Rockenbaugh.

posted 6:25 PM | 0 comments

Monday, January 19, 2004

More Wonder Boys

Crabtree and I had discovered the Hi-Hat together, in the course of one of his first visits to Pittsburgh, during the period between my second and third marriages -- the last great era of our friendship, of our pirate days, before stars were lost from certain constellations, when the woods and railroad wastes and dark street corners of the world still concealed Indians and poetical madmen and razor-sharp women with the eyes of tarot-card queens. I was still a monstous thing then, a Yeti, a Swamp Thing, the chest-thumping Sasquatch of American fiction. I wore my hair long and tipped the scales at an ungraceful but dirigible two hundred and thirty-five pounds. I exercised my appetites freely, with a young man's wild discipline. I moved my big frame across the floors of barrooms like a Cuban dancer with a knife in his boot and a hibiscus in the band of his Panama hat.

We found Carl Franklin's Hi-Hat, or the Hat, as it was known to regulars on the Hill, stranded in a forlorn block of Centre Avenue between the boarded-up storefront of a Jewish fish wholesaler and a medical supply company whose grimy display windows featured, and had gone on featuring ever since, a miniature family of headless and limbless human torsos dressed up in exact, tiny replicats of hernia trusses. On the avenue side there were only a fire door and a rusted sign that said FRANKLIN'S in looping script; you got in through the alley around back, where you found a small parking lot and a large man named Clement, who was there to look you over, assess your chracter, and pat you down if he thought you might be packing. He didn't come off as a very nice person the first time you met him, and he never got any friendlier. The owner, Carl Franklin, was a local boy -- he'd grown up on Conkling Street, a few blocks away -- who'd worked as a drummer in big bands and small combos during the fifties and sixties, including a stint in one of the late Ellington configurations, and then come home to open the Hi-Hat as a jazz supper club, aiming to attract a class clientele. There was a beautiful old Steinway grand, a luminous bar of glass brick, and the walls were still hung with photographs of Billy Eckstine, Ben Webster, Errol Garner, Sarah Vaughan; but the place had long since devolved into a loud R&B joint, lit with pink floodlights, smelling of hair spray, spilt beer, and barbecue sauce, catering to a shadowy, not particularly sociable crowd of middle-aged black men and their ethinically varied but uniformly irritable dates.

I remember that I had been dangling unhappily from the rope of my new life as an English professor in Pittsburgh for about three months, friendless, bored, and living alone in a cramped flat over a Ukranian coffee shop on the South Side, when Crabtree showed up, dressed in a knee-length leather policeman's coat, with a sheet of Mickey Mouse acid and sixty-five hundred dollars in severance pay from a men's fashion magazine that had just decided to fire its literary editor and get out of the unprofitable ficiton business once and for all. I was so glad to see him. We set out immediately to reconnoiter the bars of my new hometown -- Danny's, Jimmy Posts's, the Wheel, all of them gone now -- landing in the Hat, on a Saturday night, when the Blue Roosters, the house band at that time, were joined onstage by a visting Rufus Thomas. We were not only drunk but tripping our brains out, and thus our inital judgement of the welcome the Hat afforded us and of the level of the entertainment was not entirely accurate -- we were under the imprression that everybody there loved us, and as I recall we also believed that Rufus was singing the French lyrics of "My Way" to the tune of "Walkin' the Dog." At a certain point in the the evening, furthermore, one of the patrons was badly beaten, out in alley, and came stumbling back into the Hat with his ear hanging loose; Crabtree and I, having consumed four orders of barbecued ribs, then spent a fiery half hour unconsuming them, taking turns over the toilet in the men's room. We'd been going back ever since, every time Crabtree came to town.

Those of you who have been paying attention probably notice Chabon's technique of showing two sides of a coin: first illustrating the great attractiveness and virtue of a subject in order to get the audience to invest themselves in its fate, only to undermine that with an account of its seedy underside. I find this character-building technique very appealing. We all start off with great intentions, worthy of admiration on the basis of our theoretical idealizations. Then we succeed and fail, often in alternating measure, as factors outside of our control and a general wearing-down of our souls derail our lives from their perfect vision. It is this derailing -- the colorful breakdown of the sleek Bauhaus designs of youth into wrinkled complexity -- that is unique to each character and ultimately comprises the stories worth telling.

posted 1:47 PM | 0 comments

Tuesday, January 13, 2004

And the "Favorite Book Character Cameo Award" goes to ...

The teacher was a real writer, too, a lean, handsome cowboy writer from an old Central Valley ranching family, who revered Faulkner and who in his younger days had published a fat, controversial novel that was made into a movie with Robert Mitchum and Mercedes McCambridge. He was given to epigrams and I filled an entire notebook, since lost, with his gnomic utterances, all of which every night I committed to the care of my memory, since ruined. I swear but cannot independently confirm that one of them ran, "At the end of every short story the reader should feel as if a cloud has been lifted from the face of the moon." He wore a patrician manner and boots made of rattlesnake hide, and he drove an E-type Jaguar, but his teeth were bad, the fly of his trousers was always agape, and his family life was a semi-notorious farrago of legal proceedings, accidental injury, and institutionalization. He seemed, like Albert Vetch, simultaneously haunted and oblivious, the kind of person who in one moment could guess, with breathtaking coldness, at the innermost sorrow in your heart, and in the next moment turn and, with a cheery wave of farewell, march blithely through a plate-glass window, requiring twenty-two stitches in his cheek.

Wonder Boys by Michael Chabon

Whenever I pick up Wonder Boys, and I do pick it up quite often, I'm reminded of why I love writing and writers and the kind of people who love both. Chabon's voice is so lyrical and sentimental, so generous and loving towards its subjects, that I can't help but feel inspired to keep on practicing my feeble talents, initially corn-fed on 5-paragraph short-story analysis in highschool, torqued this-way-and-that through two years of horribly overwritten Blog essays, and finally settling down in the none-too-prestigious, yet lively, neighborhood of scriptwriting.

Incidentally, isn't "farrago" by far the coolest new word you've come across in a long time? Say it, write it, sneak it into your daily diction whichever way you want, but Good God, that's some tasty verbiage.

*smacks lips*

posted 11:53 PM | 0 comments

Friday, January 09, 2004

Time Travel

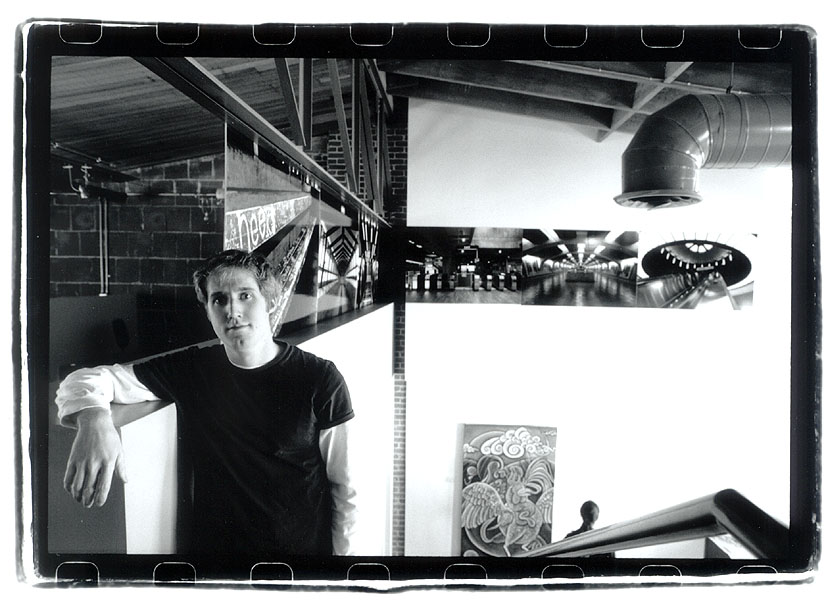

Finally, nearly two years after the fact, I post a metaphoto of my first (and to this date, only) Gallery showing of my work. Ah, the memories ...

posted 12:00 AM | 0 comments

Wednesday, January 07, 2004

All this Unearned Unhappiness

The director of “House of Sand and Fog,” Vadim Perelman, is an expatriate himself. He was born in Kiev, grew up in Canada, and moved to Los Angeles, where he made music videos and TV commercials. This is his first feature film. His work is quiet and steady, but, like Jane Campion’s recent “In the Cut” and Alejandro González Iñárritu’s “21 Grams,” Perelman’s movie offers a malign and depressive view of life in America—a place where people can discover their souls only though misery and mess. Working with generally good actors, these three foreign directors created small, dense networks of relationships, and their sense of concern comes as a relief in our increasingly anti-humanist commercial cinema, where spangled fantasy is the norm. The trouble is, as talented as these directors are, they don’t really get America right. They don’t provide a flow of activity around the core relationships; they miss the colloquial ease and humor, the ruffled surfaces of American life. “In the Cut” is set in a paranoid, mouth-of-Hell version of New York, “21 Grams” in a nameless urban and rural wasteland (it’s as if the landscape were so fouled it repelled an identity), and this movie, too, rattles angrily in a vacuum. Campion, Iñárritu, and Perelman may be complacent in their own ways. Perhaps they accept tragedy too easily; perhaps they need to work harder to make it seem unavoidable. Dolorousness is becoming a curse in the more ambitious movies made in America by foreign-born directors. We need criticism and satire. We don’t need other people’s despair.

- From David Denby's New Yorker review of "House of Sand and Fog"

I haven't seen - and probably won't attend - "House of Sand and Fog" for this reason: I'm tired of these overly-gritty movies masquerading as "realist" cinema. I even walked out on "21 Grams" after the first 30 minutes or so.

When are folks going to learn that heavy does not equal profound and that the best way to plant an idea in the moviegoer's mind is via the medium of laughter? Just talk to any memory expert: we remember what we enjoy and block out the rest. I honestly can't recall much of anything I saw in "21 Grams," mostly because I wouldn't want to.

The same goes for "Lilya Forever," John Frankenheimer's incredibly pretentious "Seconds," and "Requiem for a Dream." Those movies are especially bad because they violate you to the core with all their unearned over-the-top shock-value. The only things that I want to jolt me around like that are the real thing, not some staged 12th take of a heroin addict spotlit with a 650-watt Inky-Dinky and filmed with a Panavision Platinum on a crane dollying back smoothly across 30-feet of stainless steel track. Whenever I see such "real" scenes, I can just hear craft services pouring more M&M's into the cut-glass serving bowl...

posted 1:21 AM | 0 comments